Prenatal substance exposure and early life experiences have a powerful impact on brain development, but only a few studies to date have researched the effects of both prenatal substance exposure and adverse childhood experiences on mental health and behaviour. The results of this study show that mental and behavioural disorders occur twice as often in exposed as in non-exposed individuals. However, the difference between the exposed and unexposed individuals diminishes when adverse childhood experiences are considered.

There is no complete record of the prevalence of substance use during pregnancy in Finland. The estimate is that about 6 percent of women in Finland use substances during pregnancy, but heavy abuse gets rarer and decreases further into the pregnancy. However, later studies have concluded these numbers to be underestimations.

Earlier studies have consistently shown that prenatal alcohol exposure causes cognitive and behavioural dysfunction, congenital anomalies, as well as both long- and short-term morbidity. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure impact the development of learning and memory, motor function, attention, and language.

These symptoms and their origin are diagnostically gathered under the umbrella term Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, or FASD. In turn, prenatal drug exposure has not been reported to cause serious neurocognitive or somatic dysfunction compared to alcohol. However, prenatal drug exposure does increase the risk of obstructed language development, problem solving, attention problems, and abstract reasoning.

Studying the effects prenatal substance exposure is difficult for several reasons. First, combined substance use is common among pregnant women with substance abuse problems. This makes it hard to separate the effects of the substances, which means that the research observations might reflect the impact of multiple exposures. Second, many of the complications of prenatal substance abuse are associated factors that are risks in of themselves, like low birth weight, poverty, and a poor caregiving environment. This further complicates the separation of correlation, cause, and effect. Finally, it is difficult to reach representative samples since many mothers may not be aware of their pregnancy and unwittingly expose the foetus, others might not want to participate in studies because of the stigma of substance use, while some are simply not reached. This constitutes a problematic sample bias to account for.

In other words, research into the effects of prenatal substance abuse need to integrate a multidisciplinary approach, where both genetics, prenatal and neonatal medicine, psychology, and environmental factors are incorporated.

The research group consisting of scientists from the Folkhälsan Research Center, HUS, THL, and STM, led by Adjunct Professor of Social Psychology Anne Maarit Koponen, conducted a longitudinal cohort study based on a medical records from HUS and other available register data banks.

The aims were twofold. Firstly, to compare the nature and extent of diagnosed mental and behavioural disorders among youth with prenatal substance exposure compared with a control group of unexposed individuals. Second, to investigate the influence that prenatal substance exposure, health status in infancy, and adverse childhood experiences have on diagnoses of mental and behavioural disorders.

The data consisted of 615 exposed individuals in the ages 15-24 and 1787 comparable unexposed individuals as a control group. The researchers used descriptive analyses and Cox regression analysis to explore the data. Descriptive analyses produce overviews of data, like distributions and means, while regression analysis is used to examine the influence that variables have on each other and pinpoint which factors that matter most.

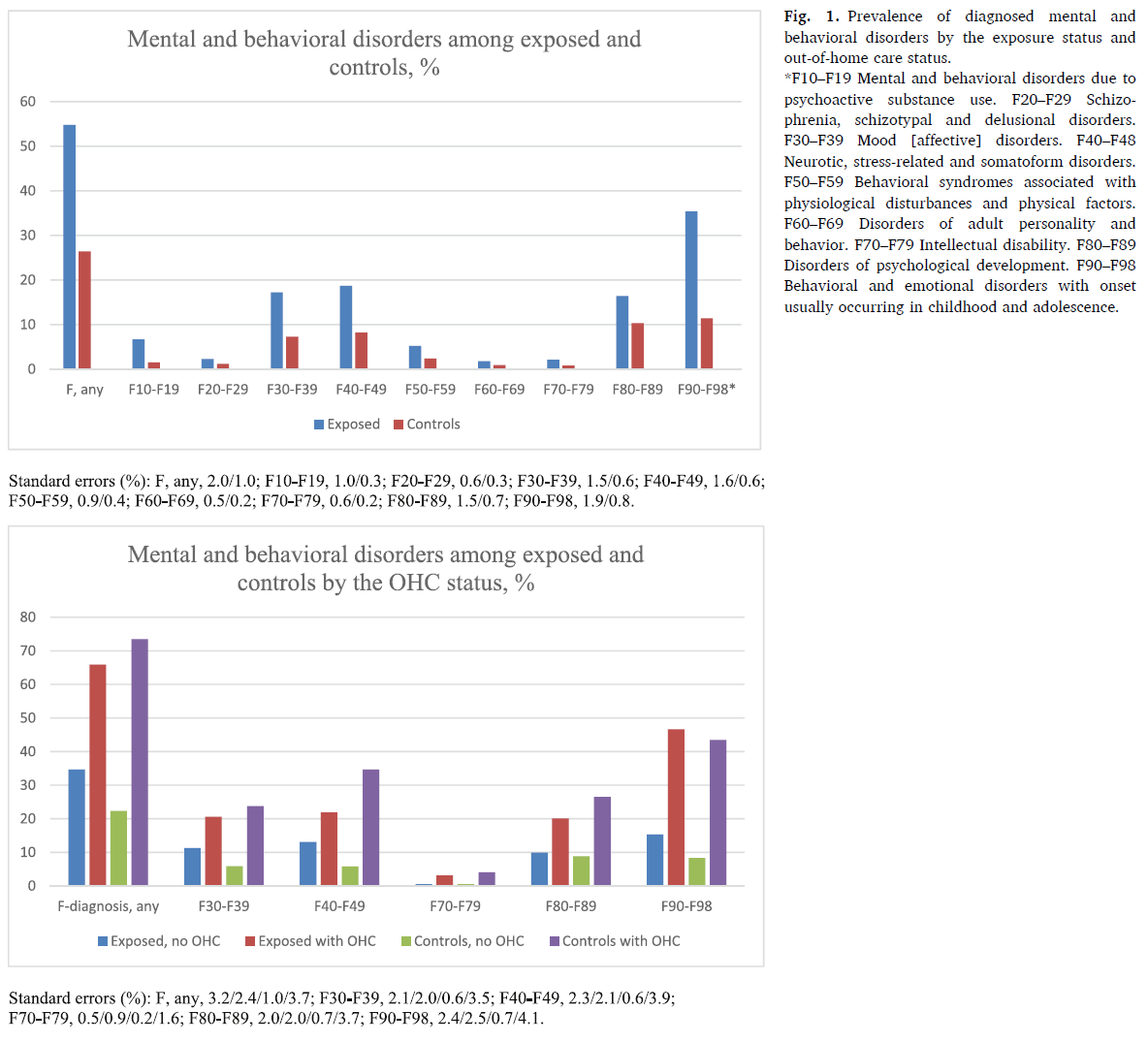

The results showed that mental and behavioural disorders occurred twice as often in the exposed individuals compared to the unexposed in the control group. Mental and behavioural disorders and adverse childhood experiences were mostly found in exposed individuals who had been taken to out-of-home care at least once.

However, the rates of mental and behavioral disorders were also high among unexposed with out-of-home care experiences, but 64 percent of the exposed individuals had been taken into custody at least once, while the same number among the control group was only 8 percent. Out-of-home care was strongly correlated with risk factors connected to the mother and other environmental factors. A minority of the exposed individuals had never ended up in custody, and this suggests that the mother’s substance abuse problems and other problems had been less severe in these cases.

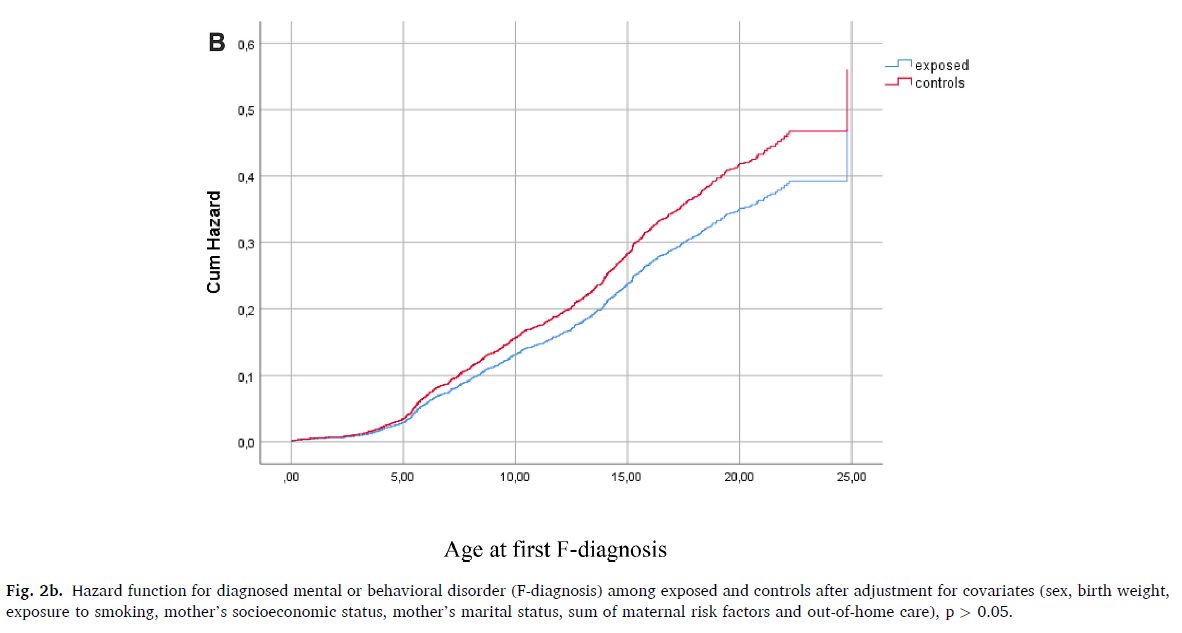

When the effect of adverse childhood experiences was accounted for the difference between the exposed and unexposed individuals diminished. As such, low birth weight, maternal risk factors, and out-of-home care were the strongest predictors of mental and behavioural disorders, which suggests that prenatal substance exposure alone cannot explain the poorer mental health observed among exposed youths.

This study emphasises the need for preventive action to minimise the detrimental effects of prenatal alcohol and drug exposure. Suggested approaches include intervention within primary education, pregnancy follow-up on women with substance abuse problems, continued treatment after birth, and support mechanisms for the whole family all the way from the prenatal period into adulthood.

• Mental health problems are common in youth with prenatal substance exposure (PSE).

• Adverse childhood experiences accumulate among youth with PSE.

• Prenatal substance exposure alone does not predict the high rate of mental and behavioural disorders.

• Youths with prenatal substance exposure and many adverse childhood experiences had the highest risk of mental health problems.

The whole study can be read in full text here.

Simon Granroth, Science Communicator